|

||||||||||

Luchino Visconti’s adaptation of the Thomas Mann novella, Death In Venice, remains a flawed but haunting work. The film inevitably literalizes a highly philosophical and allegorical book that deals with an older man’s contemplation of youth, beauty, love, and the value of his life’s ideals in the face of his unexpected infatuation with a young boy. The movie is at its clumsiest trying to incorporate Mann’s intellectual ideas in discursive flashbacks which hope to convince us the attraction is more than sexual. Fortunately these are relatively brief, with the bulk of Visconti’s film devoted to Aschenbach’s rambling tours of a seductive, sordid Venice in pursuit of the elusive Tadzio.

The film has been derided as being too “gay.” Ken Russell included a fairly wicked parody of it in his Mahler, with a little boy swinging temptingly around train station columns before the aged composer. But what finally makes Visconti’s film so moving is that it clearly is personal. I don’t think there’s any question that this gay director was fighting many of the same demons that torment his hero, Aschenbach, who is facing artistic and physical decline. Born to an aristocratic family, the Italian Visconti had had a dazzling career in film, with many directorial successes that included La Terra Trema (1948), Senso (1954), Rocco and His Brothers (1960), The Leopard (1963), The Stranger (1967), and The Damned (1969). But Death In Venice would be his last major work and five years later, he would be dead. The film also proved to be a climax of sorts to the career of star, Dirk Bogarde. Is it any wonder Aschenbach’s hopeless love for the just-out-of-reach boy conveys real sadness—his fears of ugliness and death real sting? One of the film’s most poignant sequences is that in which the desperate composer is dyed and rouged by a barber into a pathetic parody of youth. “There is no impurity so impure as old age.”

Death In Venice is surely one of the cinema’s most languorous and luxurious visual achievements. The sun-struck close-ups of the boy, which are obviously intended to recall Mann’s evocations of Apollo, are especially breathtaking. 15-year-old Bjorn Andresen played pretty boy Tadzio. Andresen made no other major pictures and quickly slipped into obscurity, allowing him to remain ageless in memory, the embodiment of eternal youth and perfect beauty. For anyone who was gay or coming out in 1971, when it was still so rare for a film to even touch upon the subject of homosexuality, Death In Venice invariably made an indelible impression.

“Luchino Visconti occupies a unique place in history of world cinema; he is the most Italian of internationalists, the most operatic of realists, and the most aristocratic of Marxists. Although one of the progenitors of the Italian neorealist movement, Visconti, with his love of spectacle and historical panorama, would seem to have more in common with Orson Welles or even Erich von Stroheim than with Rossellini or DeSica. Directors as diverse as Bertolucci, Scorsese, Coppola and Fassbinder have named him as a major influence.”—Ruth McCormick, The Encyclopedia of Film

“One of the themes of Mann’s brilliant novella has to do with the artist’s recognition of the power and validity of physical beauty, and Visconti’s cinematic approach conveys his understanding of this theme in every frame. The splendor of Venice, the elegance of Aschenbach’s seaside hotel, the androgynous perfection of the boy Tadzio—all are photographed in a lush, unhurried manner that allows the viewer to linger on a detail or to simply absorb the richness of the scene as a whole. This is a story—and a film—of contemplation, and Visconti permits his audience to share in the overwhelming sensuality that will penetrate Aschenbach’s emotional reserve and shatter his lifelong convictions about philosophy and art.”—Janet E, Lorenz, The International Dictionary of Films and Filmmakers

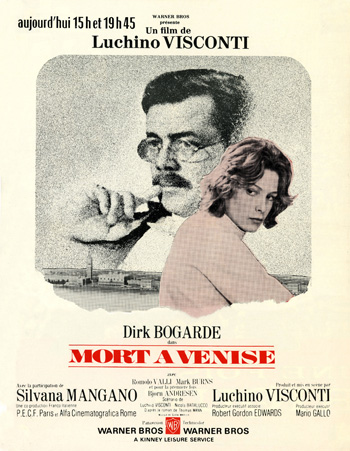

At right, Death In Venice memorabilia from the Teegarden/Nash Collection: a movie still (Silvana Mangano & Andresen), mini lobby card (Andresen & Bogarde), magazine ad, and frame enlargement (Andresen & Bogarde).

—John Teegarden

This article originally appeared in Audience Magazine (AudienceMag.com).![]()