|

||||||||||

Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton were the most famous couple in the world, in 1966 (some might say, most notorious, following their scandalous romantic entanglement on the Cleopatra set, some years earlier). In all, they starred in over a dozen movies together, largely of disappointingly dubious merit—The VIP’s, The Sandpiper, Taming of the Shrew, Boom, etc. For the most part, they made better pictures in the company of others. Surprisingly, their enduring triumph as a couple would prove to be their riskiest venture, Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? The film was based on an Edward Albee play boasting adult themes and language that would shatter the movie Production Code and helmed by a stage director making his film debut, Mike Nichols. It also provided Taylor—a star better known for her tantalizing looks than her acting ability—with her most challenging and unlikely role, playing the slatternly wife of a middle-aged college professor. But for once, the project seemed to fully engage the wild Welshman and violet-eyed beauty.

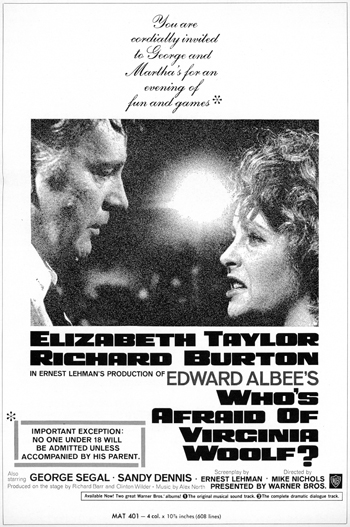

Public curiosity was piqued by a tightly closed set, press reports of Taylor’s deliberately deglamourized appearance (gaining weight, letting her hair go gray), and a unique no-one-under-18 admissions policy. “You are cordially invited to George and Martha’s for an evening of fun and games,” the ads famously proclaimed. Some audiences were shocked, but few were disappointed. Being an underage teen at the time, I remember quite distinctly being forbidden to see Virginia Woolf. Of course, once I was away at college and out of parental control, I caught up with the picture at first opportunity. Since then, it has always ranked near the top of my favorite films list.

I have a soft spot for movies with lacerating dialog and powerhouse performances—like All About Eve and Lion In Winter, to name a couple of others. Woolf’s language was well beyond the bounds of propriety. Still, it circumvented the many censorious bodies of the time thanks to its obvious artistic integrity and self-imposed audience restrictions. Life magazine duly tallied the film’s offenses: eleven “goddamns,” seven “bastards,” five “sons of bitches,” and assorted colorful phases such as “screw you,” “up yours,” and “hump the hostess.” In retrospect, you could say Virginia Woof has a lot to answer for.

Taylor won the Best Actress Oscar for her performance and most would agree (unlike her Butterfield 8 statuette) this was a well-deserved accolade. Not only did the star seem to revel in the chance to cast off her glamour-girl image, but also to fully understand Martha’s rage and sorrow; her savage disappointment in life and love. Many felt Burton should have taken home an Oscar as well for his less showy, but no less deeply felt performance as husband George. (Fellow Brit Paul Scofield beat him out with A Man for All Seasons.) Despite seven nominations, this highly regarded actor never did take home the gold. Ernest Lehman’s screenplay, Mike Nichols’ direction, and the film itself were all also bested by the decidedly more genteel (and safer) Seasons.

Clearly Nichols—who would go on to do The Graduate, Catch 22 and Carnal Knowledge in the following few years—deserves a lot of credit for the film’s success. Not only did he coach these egocentric stars into giving what may be their best screen performances, but he orchestrates the play’s tricky score of laughter and tears, storm and calm, with masterful confidence. He makes the most, not only of the big moments, but of the small ones too. From the suspenseful intro of Taylor and Burton, starkly revealed out of the shadows of the night (“What a dump!”) to a gnawed chicken bone nonchalantly returned to the refrigerator (“Chicago was a ‘30s musical starring little Miss Alice Faye, Don’t you know anything?”) to a comic ballet of blinking turn signals (“Clink, clink.”).

At right, artifacts of the sensational Woolf from the Teegarden/Nash Collection: movie still, Life magazine cover, newspaper ad matt, and lobby card.

—John Teegarden

“In their previous films together, [the Burtons had] let the public see how love overcame all obstacles, or at least made the sacrifice worthwhile. Now with anti-romantic tempers at full throttle, they were set to land blow after blow on each other’s weaknesses. The roles were in some ways a bit too close for comfort. Like George and Martha, they drank liquor to excess; they played games with each other in front of friends or strangers; they fed each other’s fantasies, slipping in and out of the roles they had manufactured for themselves: as adulterous lovers, as husband and wife, as movie stars, as a theatrical couple, as nomadic millionaires, as eternally newsworthy celebrities. They enjoyed the punishment George and Martha inflicted on each other. They heard in it an echo of their own temperaments.”—Alexander Walker, Elizabeth: The Life of Elizabeth Taylor

This article originally appeared in Audience Magazine (AudienceMag.com).![]()