|

||||||||||

I find it instructive to remember that Vertigo was not much liked at the time of its original release (1958). Reportedly the New York Times dismissed the picture as “all about how a dizzy fellow chases after a dizzy dame.” There were no Academy Award nominations—much less awards (Gigi was their pick). No New York Film Critics Circle prizes (The Defiant Ones was the favorite). Vertigo didn’t even manage to make the National Board of Review ten best list (which did very generously include Windjamer, The Goddess, The Brothers Karamazov and a Danny Kaye flick titled Me and the Colonel). If I can trust The Encyclopedia of Movie Awards, at the box office Hitchcock’s masterwork only ranked a middling 21st for the year (bested by Peyton Place, The Vikings and Old Yeller, amongst others). One can argue that Vertigo may have been too passionate and too personal for the pre-auteurist 1950s. Perhaps contemporary audiences were also put off by a hero who is met hanging from a gutter and left standing at the edge of the abyss. At the other extreme: in the most recent Sight & Sound critic’s poll Vertigo displaced Citizen Kane to be named the greatest film of all time.

I’m assuming you know Vertigo’s plot, very loosely based on a French novel by the authors of Diabolique. In case you don’t: James Stewart plays Scottie Ferguson, a San Francisco police detective who’s retired from the force because of his vertigo—deathly fear of heights—which has accidentally caused the death of another officer. Scottie is hired by a smooth school chum to keep tabs on his wife, who he claims has been behaving peculiarly and may be possessed by the spirit of a suicidal ancestor. Scottie is rightly skeptical. But as he follows this cool blonde beauty, Madeleine (Kim Novak), wandering from graveside to gallery to ghostly boarding house, he quickly falls in love with her. After he rescues her from a deathly plunge beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, Madeleine starts to fall in love with him too. Still Scottie is unable to save her when she unexpectedly races up a mission tower and plunges to her death. Scottie is wracked with guilt and despair. Sometime later, he spots a sales girl with a striking resemblance to Madeleine. Brazenly following her home, he begins to romance and remake her in his love’s image. But it’s more than mere chance that Judy Barton (also Novak) looks like Madeleine—as Scottie discovers with tragic consequences for them both.

Vertigo is actually more fascinating to watch once you know it’s “secret,” which Hitchcock quite deliberately gives away two thirds of the way into the picture—confirming he intends it to be more psychological romance than mystery thriller. If you don’t want to know, read no further: Judy is Madeleine—was coached to play Madeleine in a very clever (and I’ll admit unlikely) murder plot. What wasn’t part of the scheme was that Judy falls in love with Scottie as much as he falls in love with Madeleine. Once you realize this, the first half of the film becomes doubly poignant and Kim Novak’s underrated performance all the more finely nuanced and moving. You’re never quite sure when Judy is just playing Madeleine being in love with Scottie and when she’s saying what she’s really feeling. The wrenching scene before she makes her fateful run up the mission tower I read as mostly all Judy—the kiss that she knows will be their last, her parting words, “It wasn’t supposed to happen this way. It shouldn’t have happened & You believe I love you. Then if you lose me, you’ll know I loved you and want to go on loving you.” .

For me Vertigo is much about the illusions of love. At some point during my numerous viewings of the film, I realized that Madeleine, the woman our hero, Scottie, is so desperately in love with, in fact does not exist. This ghostly blonde beauty is the creation first of Galvin Elster, to camouflage the murder of his wife, and later of Scottie himself, who remakes Judy Barton into the image of his ideal. Madeleine can be Scottie’s perfect love because he doesn’t really know her. Mysterious, elusive and terribly vulnerable, she can be all he wants and imagines her to be. It is pointed and poignant that he has little interest in the flesh and blood women who do care for him. He can only love Judy when he’s changed her into Madeleine. And poor Midge (so touchingly played by Barbara Bel Geddes). Clearly she’s waited around for ”Johnny-O” to make his move for years. As a joke, she paints her face on the portrait of his ideal. But Scottie doesn’t think it’s funny—at all. We see Midge for the last time in a lingering long shot, walking alone down a long, dark corridor. We can guess she’s realized she’s never going to meet the standards of Scottie’s romantic dreams; that he’s never is going to love her back. It’s one of the film’s most haunting moments.

I can’t end this without mentioning Bernard Herrmann’s splendid score—in my book one of the most memorable and effective ever written for a film. (Hard to believe the Academy overlooked even this!) It sustains the movie’s tension through leisurely passages of watching and ”wandering,” before bursting into great voluptuous swells of musical passion.

One likes to think that film classics like Vertigo will inevitably endure and be rediscovered, despite initial disinterest or disparagement.

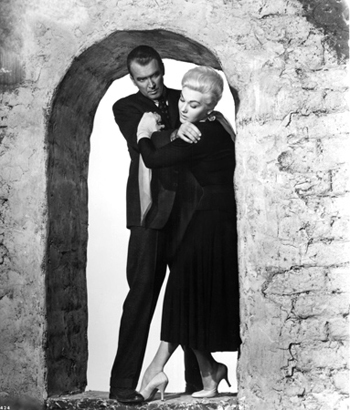

At right, Vertigo memorabilia from the Teegarden/Nash Collection: an insert-style poster, movie still, contemporary German lobby card and second still (Stewart & Novak in all).

—John Teegarden

This article originally appeared in Audience Magazine (AudienceMag.com).![]()