|

||||||||||

Cinerama was the first, most ambitious and least practical of the wide screen processes that came into use in the early 1950s, when the movie industry was desperately trying to combat the growing popularity of television. The premiere feature made in the format was This Is Cinerama, which opened in 1952, excited great public interest, and became a huge box office success. (The first commercially distributed motion picture made in the 3-D process, Bwana Devil, perhaps not coincidentally, was released that same year.) The debut of CinemaScope followed in 1953 with the release of The Robe. Rival wide screen processes—like VistaVision, Panavision, Superscope and Todd-AO—following shortly thereafter, sounding the death knell of the relatively square 1.33:1 aspect ratio which had been the industry standard for decades.

Cinerama consists of three separate images shot and projected side by side to create one large, wide picture. The three cameras that hold the film were set at a slight angle to one another and the film was projected on a screen with a deep 146º curve, with the intention of simulating and filling the human field of vision. The problems inherent to the system were many. The Cinerama cameras were heavy and cumbersome and did not lend themselves either to panning or close-ups. Theaters had to be specially equipped to show the format (reportedly, at its peak of popularity there were a mere 174 worldwide). Seams between the three panels were almost unavoidably visible. Even more troublesome, should one of the projectors showing the film go out of sink with the other two, the illusion was spoiled. Nevertheless, the effect was undeniably unique and genuinely thrilling, most famously exemplified by the literally breathtaking rollercoaster ride in This Is Cinerama.

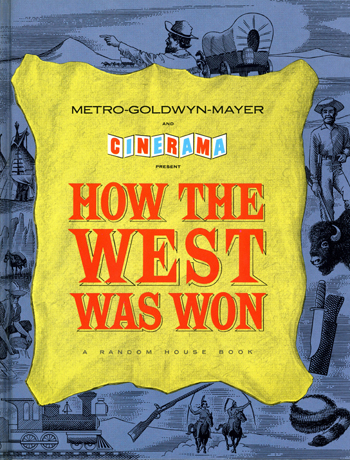

True Cinerama survived barely more than ten years, before its expense and impracticality caught up with it. In all, only ten features were made in the format (including a couple shot in competing processes, the superior Cinemiracle and Soviet Kinopanorama). Most were little more than large-scale travelogues, like Cinerama Holiday (1955), Seven Wonders of the World (1955), Search for Paradise (1957) and Cinerama South Seas Adventure (1958). Only two traditional story films were made in the process, The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962) and How the West Was Won (1963), which was ironically the best and last Cinerama film. The Cinerama logo appeared on a few other pictures through the late 1960s—including Grand Prix, It’s a Mad Mad Mad Mad World and 2001: A Space Odyssey—but they were shot in single-camera 70mm.

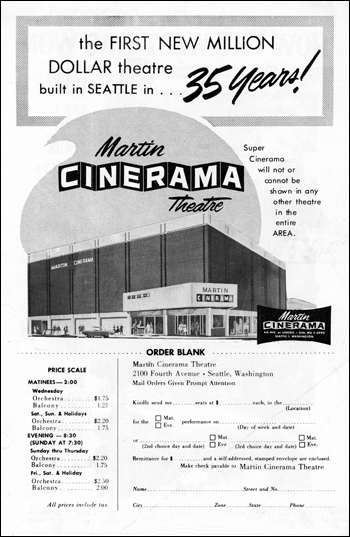

Thanks to the philanthropy of Microsoft multi-millionaire Paul Allen, Seattle lays claim to having the world’s sole surviving Cinerama theater. (The Cinerama Dome in Hollywood was built late in the game and only recently retrofitted to showcase the process.) Local movie fans are currently being treated to a two-week festival of Cinerama and 70mm films, led off by a meticulously restored print of HTWWW. I can’t adequately describe the wave of nostalgic emotion that swept over me, seeing a pristine print of this film in Cinerama, in the same theater I’d first seen it in as a child almost fifty years ago. Talk about time travel!

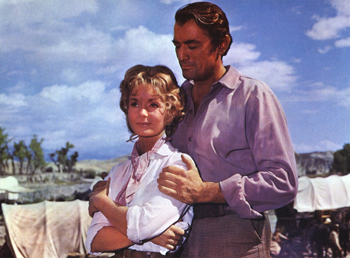

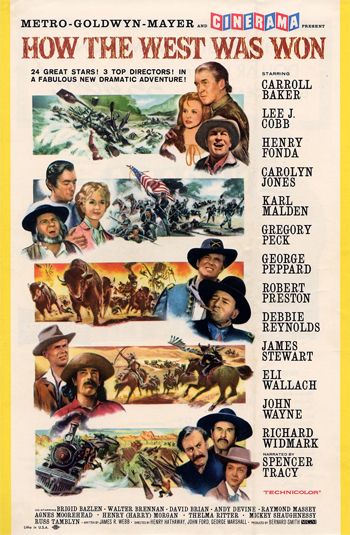

I don’t think anyone would claim that How the West Was Won is a great movie. But few would deny it’s great fun. It attempts to tell the epic story of the settling of the West by following three generations of the Prescott family as they travel up the Eerie Canal and by a wagon train across the plains to California. Included are the Gold Rush, the Civil War, and the building of the transcontinental railroad; river rafting, an Indian attack, buffalo stampede, and train robbery. The roster of stars boasts James Stewart, Gregory Peck, Henry Fonda and inevitably, John Wayne—with narration by Spencer Tracy. There are even a couple of musical numbers featuring Debbie Reynolds! In all, it took three directors to helm this mammoth project, Henry Hathaway, John Ford, and George Marshall, each laying claim to one section of the film. (One of my all-time favorite screen credits reads: “The Civil War directed by John Ford.”)

It’s a Hollywood production all the way, concluding rather dubiously with the L.A. freeways exemplifying the panicle of our civilized achievement. There’s so much history and action, even the big Cinerama screen can’t quite contain it. Few of the stars really have a chance to register, though Stewart’s charm breaks through and Reynolds’ twinkle adds a mischievous spark to the proceedings. The film’s most emotional moment is provided by a classic Ford image: a mother kneeling in prayer beside her parents’ graves as her eldest son goes cheerfully off to war. I must also mention Alfred Newman’s music, which manages to be rousingly epic as well as lyrically intimate and is quite simply one of the finest film scores ever written.

If you’ve only seen HTWWW on video or in a reconfigured standard screen version, you haven’t really seen it. Perhaps because of the depth and size of the curved screen (30 x 90 feet in Seattle)—perhaps because the three conjoined images really do fill your field of vision, Cinerama does create an enveloping, you-are-there sensation unlike any other movie format. Many thanks are due Allen and the Seattle Cinerama folks for their part in preserving this rare and unusually entertaining piece of cinema history.

“To the pounding of buffalo hoofbeats the water tank comes crashing down. As catastrophic as it might look, it is all part of the building of the West, as seen from Hollywood. With 1,200 buffaloes, 875 horses, 359 Indians, 24 stars, a cast of 12,617 players and every trick in the horse-opera repertory, MGM’s How the West Was Won is not the best western ever made but it’s surely the biggest and gaudiest. It tells the story of a pioneer family’s trek from Ohio to California, and the fussiest western fan could not point to a single missing ingredient… The movie throws in saloon brawls, intrepid marshals, gunfights, cattle drives, a wonderful train robbery, even the Battle of Shiloh, all in the elephantine embrace of Cinerama and Technicolor, with a musical score that thunders like a longhorn stampede. The big movie, suggested by a seven-part Life series, is already gunning down box-office records in London, as it will surely do in every U.S. city that does not consider it a breach of the peace.”—Life Magazine, 1963

At right, HTWWW memorabilia from the Teegarden/Nash Collection: an original handbill with the reverse promoting the newly built Seattle Cinerama Theater (top ticket price $2.50!), two movie stills (Debbie Reynolds with Gregory Peck; Jimmy Stewart with Caroll Baker), and the hardcover program book.

—John Teegarden