|

||||||||||

Fritz Lang’s Die Nibelungen (1924), with its larger-than-life heroes and villains, towering sets, and monumental ambition, is quite simply one of the most spectacular motion pictures ever made. Watching the film again recently made me wonder how much influence it may have had, directly or indirectly, on Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings trilogy. To my mind, Jackson’s Rings cycle recalls no other film quite so distinctly. Perhaps it’s just that both movies are art directed to the nth degree. But LOTR and Die Nibelungen are also both grand scale mythic fantasies of good vs. evil that richly reflect the times in which they were made.

Lang’s Nibelungen is drawn from the same stories that inspired the Richard Wagner opera, Ring of the Nibelung, though the plots are only very loosely similar. Lang is more concerned with the foibles of the humans than the gods. His nearly five-hour film is in two parts. The first, titled “Siegfried,” tells how this buff, blond hero slew a dragon, won the great treasure of the Nibelung, and claimed as his bride the beautiful Kriemhild. Their happiness, unfortunately, is short lived. In the process of wooing and winning the princess, Siegfried sets off a chain of deception and jealousy that will be the undoing of them all. In the guise of Kriemhild’s brother, King Gunther, he subdues the mighty warrior queen, Brunhild. When Brunhild discovers the ruse she’s mighty ticked off. Siegfried, you may recall, bathed in the dragon’s blood, making himself invincible—save for one small spot accidentally covered by a falling leaf. At the behest of Brunhild and Gunther, the malevolent Hagen Tronje tricks Kriemhild into betraying her husband’s vulnerability. Part two tells of “Kriemhild’s Revenge,” in which the determined princess marries the barbarian Attila the Hun in order to win his aid in punishing her clan for their treachery.

Die Nibelungen is much about love and loyalty—and betrayal. Though I confess its characters’ motivations are not always clear to me. Why, for example, do Kriemhild’s brothers choose to ally themselves with Hagen, whose many black deeds (including the cowardly assassination of Siegfied) hardly merit their devotion? Lang’s epic was a great favorite of Hitler’s and has been interpreted as a foreshadowing of the Nazi’s rise and fall from power. As a story of misguided loyalty it’s eerily prescient. Bearing the dedication, “to the German people,” Lang has said he intended the film to counteract the pessimism of the time by recalling Germany’s mythic heritage.

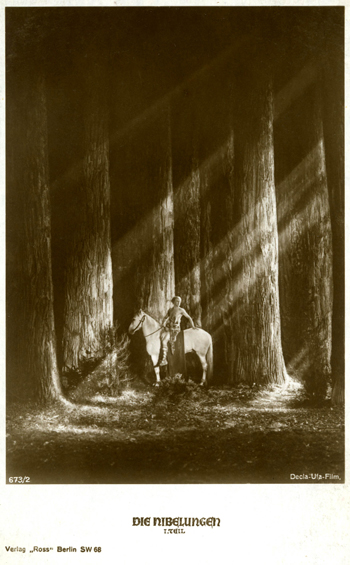

Whether or not you choose to probe the film’s social and political underpinnings, visually it’s consistently breathtaking. Lang may not have had benefit of computer imagery, but he achieves some delightful effects nonetheless—including a fire-breathing dragon, cloak of invisibility, and such poetic imagery as a flowering tree that wilts into a skull-shaped bramble, signifying the death of love. The film’s sets are legendary, including the massive trees that make up Siegfried’s forest, the sea of steps leading up to Worm’s Cathedral, and elaborately painted beams and arches that decorate King Gunther’s palace (all created on soundstages). Gunther’s servants, soldiers and kinsmen are distinguished by a deco-style angularity that defines their costumes, their highly stylized makeup, and even their hairstyles. (Brunhild and Hagen’s bird-like helmets are really quite astonishing, befitting their intimidating persona.) By contrast, the Hun’s savage court is all rounded architecture and curved decorative lines.

Director Lang’s flair for the dramatic is much of what makes Die Nibelungen a success. But at least one performance deserves to be mentioned: Margarete Schoen as Kriemhild. Her transformation from foolish girl to a woman consumed with the desire for revenge is both poignant and chilling. Wrapped in long, enveloping robes, she becomes almost literally a formidable pillar of strength. Perhaps the film’s most memorable scene is her first encounter with Attila the Hun. Even this mighty warrior (the antithesis of Siegfried in his ugliness) is so awed by her beauty and fierce determination he is humbled before her.

For the record, Lang’s other films include Dr. Mabuse the Gambler (1922), Metropolis (1926), Spies (1928), M (1931)—and after he fled Nazi Germany to live and work in the U.S., Fury (1936), You Only Live Once (1937), The Woman In the Window (1944), Scarlet Street (1945), Cloak and Dagger (1946), Rancho Notorious (1952), Clash By Night (1952) and The Big Heat (1953).

“…Die Nibelungen is a sweeping, monumental work of the most intense visual power. It represents the silent cinema in full command of its unique resources, revealing Lang as a major innovator in his use of the medium to express the psychology and inner life of his people. Backed by producer Erich Pommer, Lang had a raft of cinematographers, art directors, costume designers and special-effects technicians to enable him to create a highly stylized yet deeply evocative masterpiece.”—Kevin Thomas, The Los Angeles Times 3/24/89

At right, Die Nibelungen memorabilia from the Teegarden/Nash Collection; three vintage photo postcards: Siegfried (Paul Richter) in the forest, Siegried courts Kriemhild (Richter and Margarete Schoen), the vengeful Kriemhild (Schoen).

—John Teegarden

This article originally appeared in Audience Magazine (AudienceMag.com).